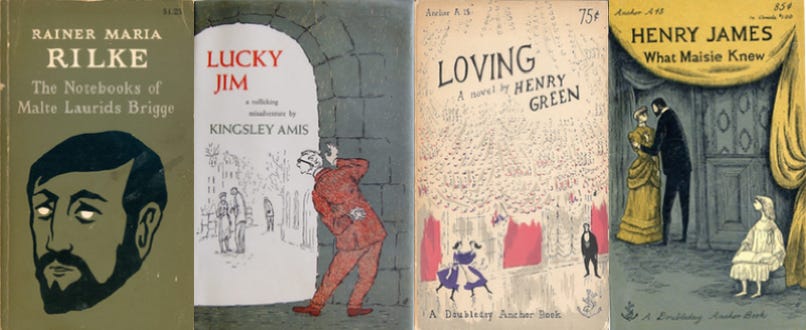

Louis Menand describes in The Free World: Art and Thought in the Cold War how in 1953 editor Jason Epstein launched for Doubleday a line of paperbacks, Anchor Books, aimed at a more discriminating readership than the mass market paperbacks of the thirties and forties and priced a little higher, from 65 cents to $1.25, and the “quality paperback” was born. By 1954, Anchor was selling six hundred thousand books a year. In 1954, Knopf launched their line, Vintage, and Beacon began one soon after. Today paperback publication usually follows hardcover publication of the same book by a year or so, except for “paperback originals,” usually aimed at a younger audience or published on tighter margins by a smaller publisher. Illus: Edward Gorey covers for 1950s Anchor paperbacks (more here)

Read the first part of this post here!

The question of how the cost of books feeds into their breadth of distribution raises related questions about e-books and libraries. The first big assault on Amazon’s monopoly power in bookselling was a 2010 effort by publishers to band together and resist Amazon’s price-gouging of e-books for the Kindle. The move was challenged by the Department of Justice and the publishers lost. The fear in the publishing industry was that consumers would think of e-books as so ephemeral that they would be unwilling to pay enough for them to support the infrastructure that goes into publishing a book. Publishers argued that the cost of cardboard and glue and paper is a small share of a book’s cost. (Hardcovers are so much more expensive than paperbacks because they are soaking the motivated buyer.) But I understand that small publishers would like to publish e-books more cheaply and are constrained by the current regime. Is the leveling off of e-books partly the work of a conservative industry resisting a less remunerative model? What does a natural balance, in availability and pricing, of hardcovers, paperbacks, and e-books look like, to preserve the pleasure of printed books that readers have undeniably clung to as well as adequate income to those who make the books and accessibility? Do the profit expectations of the corporations and high corporate salaries eat into the accessibility of books and book careers? Or is the business structurally bound to an expensive product?

Also libraries and publishers are locked in a mortal struggle over the cost of e-books for lending. Libraries pay a lot more for an e-book than you do; they lease it for a period of time and a limited number of users. Last year Macmillan dramatically curtailed library e-book access, only to reverse themselves in the face of the pandemic (Publishers Weekly explainer here). The fear among publishers is that checking an e-book out of the library has become so “frictionless” that it eats into the already narrow book market. Libraries are on the whole prepared to make some constraints on e-books: to pay somewhat more for them, and to make new books somewhat harder to check out. The question is where the balance lies.

A few other factors. I am a bit of a copyright hawk (a subject for another post), but I’m frustrated by the logjam in making out-of-print, noncopyrighted works broadly available. Surely there is a way to put resources into this that does not threaten the existing rights of creative people or give a tech giant like Google the gift of the world’s reading data. A reasoned approach to freeing up digital uncopyrighted work should be part of a balanced ecology of book sales. Similarly self-publishing has created many avenues for redirecting book revenue to people historically excluded from major publishing, but ultimately if we want a creative environment that is not 100-percent fend-for-yourself, we need structures to support the writing life—funding for the creation phase, for translation, editing, design, marketing, distribution, and supporting the long-term market with literacy programs and reading advocacy.

Book Post supports books & readers, writers & ideas

across a fractured media landscape

Subscribe to be a part of our work

Watching the disappearance of revenue from newspapers and magazines, publishers have since the arrival of digitization had a legitimate fear that books will be devalued to the point that there are no longer paying customers to support their creation, and where are we then? The durability of book-reading as a consumer phenomenon (witness BookTok, Booktube, and Bookstagram) has been a bit of a surprise to everyone. But looking to books-as-consumer-commodity or lifestyle-accoutrement as the salvation of the industry may sideline some of the more serious purposes books serve.

The book industry now relies on “philanthropy”—considered as voluntary spending by rich people—at several levels: the price of hardcovers, the low salaries of entry-level employees, the prevalence of interns, and actual nonprofits that cover the costs of many small publishers and important, low-return projects like translation. (Even public libraries are in the business of fundraising!) The fact that all the arts in America are supported by philanthropy (rather than state funding, as abroad), shapes the work that emerges from them. American philanthropy is a beautiful thing. I’ve done charitable work around the globe, and there is generosity here like nowhere else. That our philanthropic institutions want to diversify voluntarily is nice, and necessary, but if we want a more authentic culture, we need the reins of cultural power to be in the hands of other than the moneyed few.

Setting aside for a moment the question of how to get there, I would love to see someone model out a hypothetical, based on real numbers, of how we could develop financial support, and where it would be layered in, to achieve all these goals in book publishing at once (and other arts by analogy):

First-run books priced so that a broad swath of American readers can afford them, so they will be marketed to a broad swath of American readers and selected with a broad readership in mind;

Living wage for book industry employees across the spectrum, including translators;

Appropriate remuneration for authors;

Viable opportunities for bookselling in all neighborhoods, responding to community needs and supporting thriving local reading cultures;

Representation in libraries that is balanced (1) to stoke readers’ interest and serve those who can’t afford books; (2) expose readers to a broad spectrum of ideas, not just what is most popular; and (3) provide authors and book industry employees with adequate compensation;

Progress toward a universal digital library that is non-proprietary and supportive of creators’ rights.

One could think of it as a jobs program with the attendant benefit of making everything better. What would the numbers look like?

Louis Menand’s The Free World describes a moment in the mid-twentieth century when federal support of education and creative people (the GI Bill) met technologies and innovation for cheaper distribution as well as an expanding, increasingly prosperous, increasingly educated audience, creating a kind of cultural boom. That this expansion of intellectual opportunity (however reprehensibly limited) coincided with necessary liberatory movements is not a coincidence. It almost seems now like we are in an inverse situation, an economic and technical logjam keeping our culture from growing healthily to meet its audience, and an audience economically and socially barricaded from education and culture, and we see the results. Digitization is filtering money up through monopolized structures, starving creative people and the industries that support and distribute their work and bombarding the audience with commercially-driven nonsense. Clinging to an outdated revenue model, cultural decision-making is oriented toward the rich, and cultural products are channeled toward them too. How can we shake it up so the ideas can come loose and travel through the whole system? We have to look at the invisible currents of money that feed our cultural institutions, and redirect them to grow culture at everyone’s door.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in-box. Subscribe to our book reviews and support our writers and our effort to grow a common reading culture across a fractured media landscape. Recent Book Posts: John Banville on the singular caracara; Priyamvada Natarajan on the alchemy of materials science.

The Astoria Bookshop is Book Post’s Spring 2021 partner bookstore! We partner with independent booksellers to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life as it happens in their aisles. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”

Great set of articles. I am sharing them with my book groups.

Great piece.