(See Part One of this post here)

Marmee’s frenetic activity in Little Women reflects the reality of Abigail Alcott’s life, though not the fact that besides being a visionary mother she was an extraordinary political activist and keen social analyst whose knowledge of life in Boston’s industrial slums earned her a position as one of the country’s first paid social workers. No white messiah, she joined with both black and white women to found a “female anti-slavery society.” She authored two eloquent and substantial petitions presented to the Massachusetts legislature, demanding suffrage, equal legal rights, and access to jobs for women: Women “must help make the Laws, be educated as Jurists, Drs. Divine, Artists, Bankers,” she wrote, though the legislature “laid aside” the petition “with as little regard as the stump of a well worn cigar.” For a time she ran an employment agency for domestic workers, operating on principles that would be respected by today’s Domestic Workers Alliance. She vetted employers as well as employees to ensure fair wages and safe working conditions, aware of the vulnerability of household staff. Her own daughter, Louisa, had been sexually coerced during a stint as a housemaid, and cheated of her salary when she refused. No wonder Louisa often closed her letters with “Yours for reform of all kinds.”

The Alcott girls’ diet was at best frugal, though even when food was at hand they were often on the brink of starvation, eating a utopian diet designed by their father to create virtuous souls. All animal products were banned, as well as salt, cane sugar, spices, coffee, and tea. In her sardonically titled memoir of her father’s experimental community Fruitlands, “Transcendental Wild Oats,” Louisa remembers the tortuous monotony of the diet: “Unleavened bread, porridge and water for breakfast: bread, vegetables and water for dinner; bread, fruit and water for supper.” No wonder Beth dies: her immune system may very well have been compromised by a lack of vital nutrients. I lose my will to live just reading the menus. Louisa wrote that instead of consuming animal flesh at Fruitlands, the utopians devoured “only a brave woman’s taste, time and temper.” Perhaps the darkest and most desperate moment at Fruitlands was when Bronson unexpectedly trusted the “spirit” and left the harvest “to Providence,” departing the farm for other pursuits. Providence took the form of his wife and four daughters, with no other team, doing the urgent and crucial work of harvesting and storing the grain on which they had to survive the winter.

Receive our little book reviews

Subscribe for $5.99 a month, $45 a year

We support books & bookselling, writers & writing, for the digital age

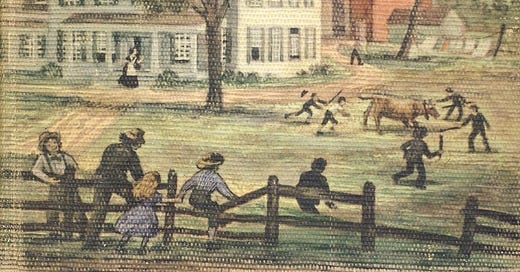

The Alcott household’s approach to food, under Bronson’s authority, was purely pedagogical. Bronson taught Louisa the concept of patience by withholding gingerbread. “Do you know what patience is?” he asked the little girl. She answered, “It means wait for gingerbread.” Little Women often reflects that moralizing use of food. Jo accepts cookery lessons after her willful domestic ignorance leads to a comically disastrous dinner; Amy’s social ambitions receive a comeuppance by way of an elegant meal of chicken, tongue, French chocolate, and ice cream that no one shows up to eat. Yet the March girls eat better food than Louisa and her sisters ever did. It is telling that the book ends with a scene of a marvelous harvest at Jo’s estate, Plumfield; every member of the three generations of the March family participates and has some role in fulfilling the gifts of the season. The day culminates with “the crowning joy of the day,” a feast in which “the land literally flowed with milk and honey,” for the boys who went to school there “were not required to sit at table, but allowed to partake of refreshment as they liked.” This scene is not simple wish fulfillment, but an act of creation, a vision of a possibility beyond her own experience. With an extraordinary generosity of imagination, Louisa’s invented harvest fed her family, and legions of readers. She made the Alcotts secure and well-nourished for generations through her novel of redemptive family love.

Patricia Storace’s most recent book is the novel The Book of Heaven, in which the intimate histories of eating and storytelling are also deeply entwined. She is also the author of Dinner with Persephone: Travels in Greece and a book of poems, Heredity. This is the latest in her series of diaries on cooking and reading for Book Post. Read the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing short and well-made book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to your in-box. Subscribe to receive our book reviews and support our writers and our effort to grow a common reading culture across a fractured media landscape. Coming soon—Robert Block: Sitting down with Radovan Karadžić, war criminal; Recently—Caleb Crain: Paul Kerschen resurrects Keats and recalls another time of contagion.

Mac’s Backs Books on Coventry, in Cleveland, Ohio, is Book Post’s current partner bookstore. We support independent bookselling by linking to independent bookstores and bringing you news of local book life as it happens in their aisles. Support your local bookstore now! Their futures are imperiled. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 at Mack’s Backs during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

A beautiful piece.

Liked this part, too, but here's my question: when did LMA write the novel? Was she still, like Jane Austen, still lodged with the family?