Notebook: 1. Isn’t it romantic?

by Ann Kjellberg, editor

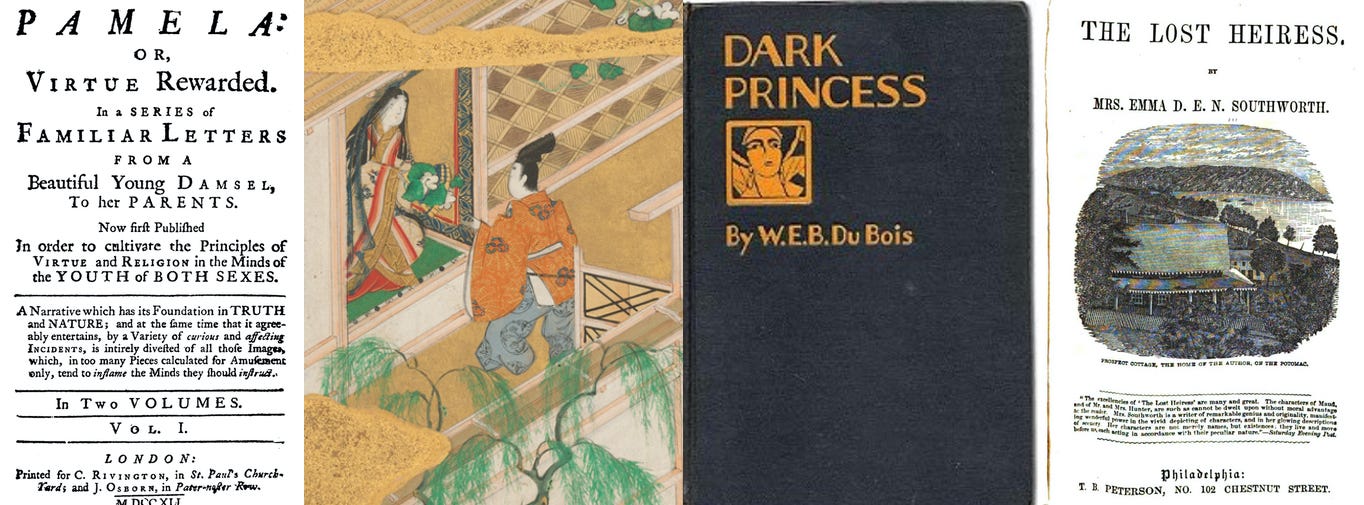

(1) Title page of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, sometimes considered the first novel in English; (2) early seventeenth-century illustration of The Tale of the Genji (Metropolitan Museum of Art) by Lady Murasaki, whom critic Harold Bloom characterized as “having anticipated Cervantes as the first novelist” with her “use of intimacy”; (3) first edition of W. E. B. Du Bois’s Dark Princess; (4) first edition of E. D. E. N Southworth's The Lost Heiress

Talking about publishing romance is like talking about publishing books, but moreso. Some people argue that the very first novels were the French romances of the early seventeenth century (“novel” in French is still “roman”). Other now-popular forms like mystery and science fiction developed generations later. Cheap paperbacks themselves had their origins in the commercial appeal of sensational, popular fiction: in the mid-nineteenth century publishers cottoned on to newly literate readers’ appetite for popular fiction and began selling cheaply printed, luridly illustrated newspaper-sized “books” through newspaper distribution on the streets and at cigar stands. As John Markert recounts in Publishing Romance: The History of an Industry, 1940s to the Present, the first US book professional to exploit the hunger for inexpensive fiction turned to romance: in 1854 T. B. Peterson published a manuscript called The Lost Heiress, by a Mrs. E. D. E. N. Southworth, that had been snubbed by establishment houses, noting an unserved appetite for “books at low prices, especially sensational fiction.” It was a hit, and inaugurated an early paperback boom of the 1880s as well as a recurrent pattern of traditional hardcover publishers declining to recognize readers’ visibly expressed appetites. When Pocket Books imitated Allen Lane’s Penguin Books in England and brought out a line of low-cost paperbacks for sale in train stations and drug stores and newsstands in the US, inventing the modern paperback (see our Notebook, “Paperback Writers”), they jumped on the same bandwagon of inexpensive production and distribution outside traditional outlets, in the places where people lived and shopped, an approach now called “mass market,” as opposed to working through booksellers, or the “trade.”

For all its commercial might, the novel continued to be derided as a “women’s” form, read in the boudoir and bound to women’s preoccupations like love and marriage while the more prestigious vehicles (and publishers) took on history and heroic deeds. Women still predominate among readers of fiction, and romance readers are the titans of them all: reportedly buying and reading hundreds of books a year and fueling (reputedly) a $1.4 billion romance industry (which may be an undercount, more on that to come). A 2018 study reported that 25 percent of all books and one out of two mass-market paperbacks sold were romance novels. As of 2016, 39.3 percent of genre fiction on the market was romance; mystery was not even close at 29.6. Washington Post book critic Ron Charles noted recently that romance giant Harlequin sells two books a second; in the 1970s and 1980s Harlequin harbored 80 percent of the world’s market share of fiction.

Romance readers are avid readers and read across genres; 50 percent of them will try a new author—a much higher percentage, reputedly, than readers of other genres. Largely because of the might of romance, women have been the driving audience for mass-market publishing. Until recently, these widely distributed books have, observers say, remained impulse buys and have attracted customers to retailers where they go on to buy other merchandise (exactly Amazon’s strategy). In a 2017 report on the state of mass-market publishing, Publishers Weekly noted that mass-market paperbacks are still favored by readers and “considered the ‘gateway’ format”: “mass-market titles are the books that turn some people on to reading, period.”

As it was, so it shall be: the power of romance as a market force continues to prompt reinvention in publishing. Romance’s defenders, who have recently become more audible for reasons we will discuss, point to the enduring power of the eclectic form’s one common denominator: the “Happily Ever After” ending (“HEA,” to afficionadas). As editor and journalist Nicole Clark wrote earlier this year, “It’s an immense comfort, especially when things are difficult in real life, to know that a main character’s needs will be met.” Elisabeth Jewell, a bookseller and romance reader at our current partner bookstore, Gibson’s in Concord, New Hampshire, told me that she had definitely seen a spike in romance reading in recent years. “People tell me, ‘I never read romance until the pandemic. It makes me happy, I’m so tired.’” In an essay on pioneering Black author W. E. B. Du Bois’s nearly forgotten romance, Dark Princess, Akil Kumarasamy wrote recently, “I realized that the genre could help us see beyond the limits of our reality, opening our minds to fantastic possibilities,” proposing that Dark Princess was Du Bois’s favorite of his own books because it “reaches for the dream”; in the words of the book, romance shows a way out of “pain, slavery, and humiliation, a beacon to guide manhood to health and happiness and life and away from the morass of hate, poverty, crime, sickness, monopoly and the mass-murder called war.”

Two more days to read a bouquet of our subscriber-only book reviews

And subscribe at our special summer rate!

Book Post promotes reading and readers, across a fractured media landscape

Romance novelist and Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams (a. k. a. Selena Montgomery) has said “romance is one of the most amazing genres to use because you have carte blanche to create any universe you want and to explore any set of archetypes and experiences with the common conversation of how people overcome their differences and find themselves in love.” She and Du Bois remind me of young adult novelist L. L. McKinney, who in 2020 launched the hashtag #publishingpaidme that disclosed yawning gulfs in the advance payments to Black and White writers, tweeting in 2021 that “a lot of Black folk, myself included, are pushing for the acquisition and equal marketing of stories about Black love, Black fantasy, Black people just living and having fun and being able to exist outside of … trauma.”

It was in fact a Black woman editor, Vivian Stephens, who says she got her romance editing job at Dell in 1978 with little relevant experience because no one at the company cared much about the work, who transformed American romance by introducing contemporary themes and less prudish descriptions of sex. “The demographics showed that millions and millions of African American women were buying and reading” romances, author Sandra Kitt told The Washington Post, but the books had no Black characters and no Black editors until Stephens came along, and few for a long time after, even now. It was only when Terry McMillan went herself around the country hawking her own books, making Waiting to Exhale a phenomenon in 1992, that mainstream publishing acknowledged the existence of a potential commercial audience for books about the romantic lives of Black women.

Romance writing as a vehicle for finding joy and well-being amidst struggle has made it a lively genre for the very marginalized groups that a hidebound publishing establishment has been slow to embrace, as John Merkert’s book repeatedly shows. Romance novelist Angelina Lopez described for the Write Minded podcast last month how her recent romance After Hours on Milagro Street allowed her to portray the joyous side of immigrant life for a Mexican-American family in small-town Kansas, with its tough-minded, not-always-skinny matriarchal clan, being both bossy and loving, striving women wrestling with the tension between home and career, for mainstream Harlequin audiences. Bookseller Laynie Rose Rizer told The New York Times that people come into her store and say, “I just want something that’s gay and happy.” Indeed Markert describes how back in 2016 publishers were a bit surprised that there was not more resistance to the rise, in response to visible demand, of LGBTQ+-themed novels for young people—the very books now being banned in school libraries across the land. Editors were finding that LGBTQ+ young adult novels about love were embraced by young people trying to envision secure, happy, and sexually grounded lives within a “sexually saturated” culture full of violence and bullying. And of course from their beginning romance novels acknowledged the aspirations of their original marginalized audience: women. Americanist Hillary Hallett, author of a new book on pioneering romance writer Elinor Glyn, put it this way: “the fundamental purpose of the modern romance when it first developed was to explore the force of women’s desire and to expose the many barriers thrown up to prevent women’s exercise of free love.”

It's perhaps not a surprise that a genre both so friendly to outsider experience and so squarely within the American social mainstream would find itself confronting turmoil around issues of diversity, most recently when the new director of the influential Romance Writers of America (RWA) resigned at the end of last year for what she insisted were personal reasons, saying however that those working on the cause were exhausted and overworked because “for 1, the world is going through it right now … Also, there are people who want to help, but won't for fear of being publicly attacked. Whichever the reason, that means that the ones who have taken on the work, work harder.” I was reminded of a powerful piece a few weeks ago in The Intercept, echoed in the New York Times’s coverage of the RWA, about divisions among generally like-minded nonprofit workers about how to advance equity in their workplaces. The RWA has been a scene of battle in part due to its own past cultures of clubbiness, and aggravated by clashing currents in the field of advocacy and money, culminating in charges of racism in 2020 and a wave of resignations and restructurings. One might argue though that such upheaval, however painful, is healthier than the self-forgiving stasis that has been the norm in prestige publishing. Novelist N. K. Jemison, writing from the adjacent genre of science fiction, which has a more openly reactionary faction, has said suggested as much.

The looming presence of the RWA in the romance world is evidence of the relative intimacy shared by the romance readership and its writership. Founded in 1980 by Vivian Stephens, the editor who was so influential in updating the industry, the RWA early on opened itself up to readers as well as writers, signaling its evolution into, sometimes, something like a sorority or a social club as well as a professional association—one of the biggest writers’ organizations in the country, according to Jezebel, bigger than the Mystery Writers of America and close to the size of the Authors Guild. During the growth of romance in the sixties and seventies, romance’s often home-bound readers aspired to be its writers too, whether for fun or to make extra money amidst limited career opportunities, and the manuscripts they bombarded the publishers with were, as Markert describes, often scooped up during times of high demand by an industry hungry for material. Harlequin held select parties for readers with authors to disclose tips, and romance publishers capitalized on correspondence with their engaged readers to be early practitioners of the newsletter. Twenty percent of the modern RWA’s ten thousand members are published writers.

This mélange of writer and reader would have enormous benefits in the most recent chapter in romance’s long story of doing the industry’s creative thinking: the flowering of self-publishing. When digital technologies began to make electronic self-publishing possible in the early 2000s, and then, titanically, when Amazon introduced the Kindle in 2007—creating a proprietary mechanism that both contained its own almost limitless distribution system and cost the writer nothing—self-publishing tore through the genres, especially romance, and opened a sluice that would decisively shift them from their slow-moving mainstream parent … [Read Part Two of this post here]

Ann Kjellberg is the founding editor of Book Post.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world.

Become a paying subscriber to support our work and receive straight-to-you book posts by distinguished and engaging writers. Coming soon! Book posts from Emily Bernard, Joy Williams, Michael Klein.

Gibson’s Bookstore is Book Post’s Summer 2022 partner bookseller! We partner with independent bookstores to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life as it happens in their communities. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”

Thank you, Ann! I loved this deep dive into romance publishing, which rarely gets its due in the lit community. I'm excited to see read part 2! Have you read Sarah Brouillette's recent Post45 article on "Wattpad's Fictions of Care"? Her research looks at how young women are reading and writing YA on the platform in ways that seem like an evolution of the romance segment you describe in your piece.

Also, a small but important (to me anyway :)) distinction: LGTBQ+ YA books aren't being "banned by school libraries." They are being banned *in* school libraries (often technically by school districts but really by conservative groups and new legislation). Libraries and librarians--another feminized and underpaid/unappreciated profession--have largely been vocal advocates for access to diverse YA and romance reads and many other critically under-valued genres they believe their communities want/need to read. I like to think of librarians as a foil to the big boys of publishing--they're the anti-lit snobs!