Notebook: 2. Isn’t it romantic?

by Ann Kjellberg, editor

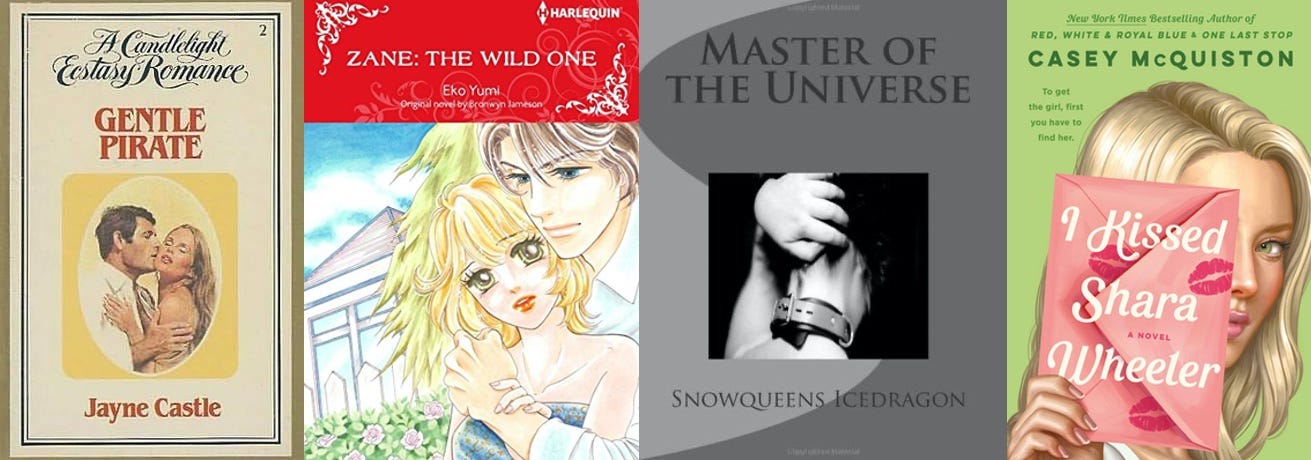

(1) Editor Vivian Stephens transformed romance when she created the more explicit “Ecstacy” line for Dell and published Gentle Pirate, a contemporary story about a romance between a wounded Vietnam veteran and a soldier’s widow; (2) Harlequin has branches around the world tailored to local tastes, like their very popular manja series in Japan; (2) the blockbuster Fifty Shades of Grey was first published serially and pseudonymously online as fanfiction of the Twilight series, was recast as an original novel called Master of the Universe, changing the names of the main characters, and published as an e-book and as a print-on-demand paperback by The Writers’ Coffee Shop, a virtual publisher based in Australia; all three volumes were on Amazon’s bestseller list when the rights were bought by Vintage in 2012; (4) Casey McQuiston discussed her new novel I Kissed Shara Wheeler as the first guest on Walmart’s live Book Club in July.

Read Part One of this post here!

The signal challenge of self-publishing is the challenge of “discovery”—the easier it becomes, technically, to publish yourself, the larger the pool of other self-published writers you must struggle to stand apart from, to be discovered by your readers. The embrace of self-publishing by romance novelists benefitted from a long history of writer-reader intermingling, like the Romance Writers Association, that connected writers directly with their readers and tapped the enthusiasm of would-be writers as an audience. (Contemporary publishing impresario Andy Hunter, inventor of the Bookshop.org website that allows independent publishers to compete online with Amazon, intuited the power of such reader-writer communities when he founded Catapult as a publisher for literary fiction as well as a hub for would-be writers, with workshops, consultancies, and community-building opportunities.) Romance also benefitted from a well-established tradition of sub-genres and what insiders call “tropes” (and others might call formulas)—historical romances, Christian romances, nursing romances, enemies-becoming-lovers romances, amnesia romances, Amish romances, the secret millionaire romance, BDSM romance (which famously got a huge boost out of a certain book originally published independently)—that pinpointed readers’ interests, making it easier for lone self-publishing writers to find their fan. These sub-genres and tropes were indeed part of what made romance so successful as a mass-market genre—readers needn’t look for individual books or authors so much as easily identified types of stories, what the industry called “category” marketing (as opposed to the inefficient “single title” marketing of trade publishing). Observers have noted that this micro-segmentation of romance has also contributed to its amenability to Tiktok, which directs users minutely in the direction of their known enthusiasms.

Self-publishing today is indeed dominated by romance. According to John Thompson’s recent Book Wars: The Digital Revolution in Publishing, between 2010 and 2018 the number of self-published books with ISBN numbers (which does not include those on Kindle, which has its own cataloguing system) went from 152,978 to 16,777,781. Amazon keeps Kindle sales a closely guarded secret (hence the question I raised above about how the widely-cited $1.4 billion number for romance sales is derived). But John Thompson looked at figures for Amazon’s closest self-publishing competitor, Smashwords, where, in 2016 at least, 50 percent of overall sales were in romance; 77 percent of sales of the top two hundred bestsellers; and 78 percent of the top fifty bestsellers. Nine of that year’s top ten bestsellers were romance. John Thompson also presented an analysis by a software engineer (and self-published writer) indicating that 47 percent of positions on Amazon’s e-book bestseller lists on a day in 2016 were held by self-published books (plus 12 percent that were from publishers so small they were likely to be self-publishers). That is an enormous number of books, unrecognized under the usual industry measures.

In the anti-trust suit against a proposed merger of publishing giants Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster, which has riveted book professionals this summer, observers acquainted with genre fiction, like Steve Axelrod, the agent who negotiated the books by Julia Quinn on which the Netflix blockbuster Bridgerton was based, were shocked (or perhaps, rather, bemused) by the assertions of publishing executives that they saw no threat to traditional publishing from Amazon’s self-publishing business. The trial is focused on the effects of a merger on a narrow band of writers of top-selling books, but these big sellers have historically included genre fiction. The trial seemed to display the elite condescension to and obliviousness of genre that has clouded mainstream publishing’s vision of their own business interests from the get-go. In documents Random House CEO Marcus Dohle said he “saw little danger in Amazon’s self-publishing activities since PRH [Penguin Random House] operated on a different quality level” and Macmillan CEO Don Weisberg testified that he “does not consider self-publishing to be a threat”; Simon and Schuster CEO Jonathan Karp acknowledged some unease about Amazon’s self-publishing enterprise based on the defection of one or two high-profile mainstream Simon & Schuster authors to publish themselves. Karp’s predecessor, though, the late Carolyn Reidy, as Steve Axelrod pointed out to me, said in a panel of CEOs at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2017 that “the romance market, which used to be huge in mass market, has pretty much dried up and gone to digital original.” “What I think every agent will tell you they’re seeing, particularly in romance, is that the midlist is completely going away in print,” one agent told Publishers Weekly that year on condition of anonymity. At the trial only Brian Murray of HarperCollins (which now owns Harlequin and is also a significant publisher of Christian romance via its various religious imprints) acknowledged that Amazon’s self-publishing wing is significant competition “on the romance front” and noted that the other Big Five are not as invested in genre as HarperCollins. (In a recent example of HarperCollins’s bullishness in the field: the Sandals resort chain announced earlier this year the formation of an “Institute of Romance” in partnership with HarperCollins to analyze “the latest global news in modern love, relationships, and intimacy … to help couples bring the sugar and spice found in their favorite books from ‘page to reality’” in their own “Luxury Included® romantic vacation.”)It has long been observed in publishing, with relief, that e-book sales, once considered a mortal threat to physical bookselling, have levelled off. But John Thompson’s study suggests that e-book sales growth has not slowed, it has just migrated to Amazon’s self-publishing enterprise, which he calls a “submerged continent” invisible to the sales data gathered by mainstream industry sources—particularly in genre, particularly in romance. Major publishers have been anxious to keep the price of e-books level with the cheapest physical books, arguing that the costs of publishing a book with a professional team are greater than the material costs of a book. But this caution has ceded the ground of the cheapest books to self-published e-books, for which authors are able to keep all the proceeds for themselves, minus the platforms’ commissions and whatever funds they put into design and marketing. Traditionally-published paperback books usually earn an author royalty of between 7 and 10 percent. Self-published romance authors have also gravitated to the freedom of self-publishing, unshackled from the preconceptions and condescensions that over the decades have characterized mainstream publishers’ often blinkered treatment of the genre. Self-published authors are not beholden to the physical book industry and cheerfully price their books to sell. Self-published $1.99 e-books are bought up in quantity by the romance readers who used to buy multiple paperbacks off the rack in a drugstore. (Another popular destination for digital genre readers are the serial sites like WattPad and Archive of Our Own and Amazon’s new Vella. In China, where government censorship of traditional publishing is tight, these platforms are wildly successful. But here, because they are not as readily monetizable as the self-published e-book, they so far seem to remain a marginal force, except in fan fiction, which cannot be monetized for reasons of copyright. Fifty Shades of Grey, which energized the more explicit end of the romance genre, first appeared on these sites as fanfiction of the Twilight series.)In the DOJ trial, mainstream publishing’s withdrawal from the market for inexpensive books was signaled by Penguin Random House CEO Madeline McIntosh, who testified that

I found that we were acquiring hundreds of books for very little advance. We were investing no marketing money to support them. We were putting covers on them that were very, very old-fashioned … we were printing these and in some cases shipping a couple of hundred, we were getting most of them back. So I made the decision with the team to significantly curtail that approach to publishing, and we regrouped. We reassessed how we could publish particularly in the romance category. And over a couple of years … we repositioned in particular [the] Berkeley [paperback imprint] as being a home to much more contemporary-feeling romance stories … with much more fashion-forward covers often in the trade paperback format.

The Publishers Marketplace industry news site, after quoting these remarks, continued, “no one connected the dots that one of the big authors PRH lost to another house—[romance tycoon] Nora Roberts—was directly related to the 2016 ‘realignment.’” What McIntosh is describing is the major publishers’ most recent strategy of taking the successfully mass-market genres like (and principally) romance, and “rebranding” them as trade paperbacks and hardcovers, to be sold in more limited numbers at a higher price in independent bookstores to a more sophisticated audience. This strategy coincided with a constriction of printing capacity in the US and a curtailment of shelf space as the bookstore chains disappeared and the big-box stores devoted less space to racks for mass market paperbacks and the magazine industry collapsed and the network of jobbers who used to distribute paperbacks alongside magazines consolidated. Steve Axelrod told me that mass-market publishers used to consider selling a million copies of a two-million-copy shipment of books out to retailers through the magazine jobbers a success. Major publishers now want to limit returns of unsold books and focus their financial commitment on a few titles they judge likely to bring in big rewards, the “top sellers” of the DOJ lawsuit. James Daunt, CEO of Barnes and Noble, one of the last remaining physical chain bookstores, has signaled recently that the store will focus more on a few orders of high-turnover titles, and will encourage local buying, rather than supporting the big, broad, nationwide purchases that used to drive mass-market publishing. Big-box stores like Walmart and Target and Costco and Sam’s Club have picked up some of the slack, but their book-buying has been erratic and provisional, not predictable enough to ground an industry based in regular bulk sales, Steve Axelrod tells me. (It’s not clear to me how the traditional mass-market rack in a department store balances with the big-box stores’ investment in first-run hardcovers, historically sometimes heavily discounted, evidenced this month for instance in Walmart’s announcement of its own book club.)

This strategic shift to bigger, more expensively produced trade paperbacks has coincided with a new appreciation of genres by independent booksellers. As booksellers have found their footing and embraced their role as hubs of local reading communities, and the audience for more commercial work has lost the vanished chains like Borders, there has been a trend among some indies toward modulating what may once have been elitism in favor of casting a wider net. As Elisabeth Jewell told me, having a romance section at Gibson’s tells the visitor that the store “supports me as a reader,” it expresses a readiness to “meet people where they are.” The more chic cover designs, embraced even by special imprints at Harlequin and other lines that formerly gravitated toward a recognizable “romance” look, make buying and toting around a romance novel less embarrassing for some. Elisabeth Jewell has created a bookmark to tabulate a book’s sexiness, both to help people find what they are looking for in the genre and also, with humor, to soften the stigma long associated with romance-reading. Romance-centric booksellers like LA’s Ripped Bodice and newcomer Meet Cute are beloved spokespeople in the indie bookstore community.

Successful romance writers are able to make decent money, and even strike gold, navigating between traditional and self-publishing and complimenting traditional marketing with inventive social media and collaborative roll-outs with their well-networked peers. In a profile of Vivian Stephens, who unaccountably lost her job and now lives in retirement in Houston, Texas Monthly quoted scholar Christine Larson to the effect that “45 percent of the romance writers she surveyed made enough to support themselves without a day job—‘that is shocking for any group of writers,’ she said.” Seventeen percent, according to her research, make more than $100,000 a year. Steve Axelrod told me he now thinks the primary relationship in a major writer’s life has moved from the agent (it used to be the editor) to their marketing person. But this path is in some ways becoming more difficult. Facebook advertising, which was key to some early successes, has become more expensive and less effective; Amazon is increasingly levering in ways to make merchant-authors pay for visibility. We’ve seen in all the social media platforms how their internal forces move from being lively public squares to agents of toxicity and disinformation.

Jennifer Long of Pocket Books told Publishers Weekly back in 2017, shortly after the consolidation at Penguin Random House that Madeline McIntosh spoke of at the trial, that “mass distribution has transitioned to efficient distribution. This means fewer returns, but also fewer books in the marketplace.” As elsewhere in the industry, all the eggs are going into the basket of a few bestselling books, even though, as PW acknowledged, “little has shifted on the consumer side. The places where mass market books are consistently bought, and the people who buy them, have not changed. Bricks-and-mortar mass merchants continue to be the outlets where these books are most popular.” To me, the move by big publishers, driven by the corporate bottom line, to invest in maximizing their return on a small affluent readership has abandoned the much broader readership that mass market once served—bringing people into the reading fold from their train stations and drugstores and grocery lines—leaving those readers to a free-for-all where they only haphazardly get the benefit of professional attention to what they read. One keeps hearing that the price of physical books is likely to go up, furthering the divide between those who are exposed to vetted reading and those who are not. Self-publishing creates wonderful opportunities, but it leaves a lot of work to the audience. The forces at work in romance publishing are, like the stories themselves, a heightened version of the rest of life, not only in book publishing but in journalism and education and the arts: market forces understood as “inevitable” are leeching the benefits of the work of culture more and more out of the world in which most people live.

We’ve considered some related themes in our Notebooks “Paperback Writers” and “Buyouts.”

Ann Kjellberg is the founding editor of Book Post.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world.

Become a paying subscriber to support our work and receive straight-to-you book posts by distinguished and engaging writers. Coming soon! Book posts from Marina Warner, Joy Williams, Adrian Nicole Le Blanc.

Gibson’s Bookstore is Book Post’s Summer 2022 partner bookseller! We partner with independent bookstores to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life as it happens in their communities. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Facebook, Twitter, Instagram

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”

Thanks, Ann! There’s a whole book’s worth of info in this post! Curious if you think publishers’ rebranding of romance titles has anything to do with the influence of Bookstagram, BookTok and BookTube (where covers sell books)? Is social media the new grocery store aisle for these titles/readers? (I’m thinking of the epic rise of Colleen Hoover.)

Also, does Thompson distinguish between romance and YA?

Our area (Southwest Virginia) has a large population of German Baptists and "old order" Brethren. A very popular section in our local library is devoted to romances with Amish characters. I've been curious about how these authors guide young hormonal readers through blossoming love. Will add a sample to my stack. Thanks for reminding me not to be a genre snob.