Notebook: Book thoughts in the age of shutdown

From Ann Kjellberg, editor

How does the current budget impasse affect the life of the book? President Trump’s first budget proposal, presented the February following his inauguration in 2017, called for the permanent elimination of the National Endowment of the Arts, the National Endowment of the Humanities (approximately $145 million each), and the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) ($231 million), which provides nearly all federal library funding, and last February’s budget proposal repeated this call. These three programs represent 0.01% of the $4.4 trillion budget, or a tenth of the $5 billion President Trump is requiring for this year’s installment of a border wall, prompting the current shutdown. Most proponents of eliminating the three agencies acknowledge that it would not realize a significant savings; they simply do not believe that government has a role in supporting the arts and ideas.

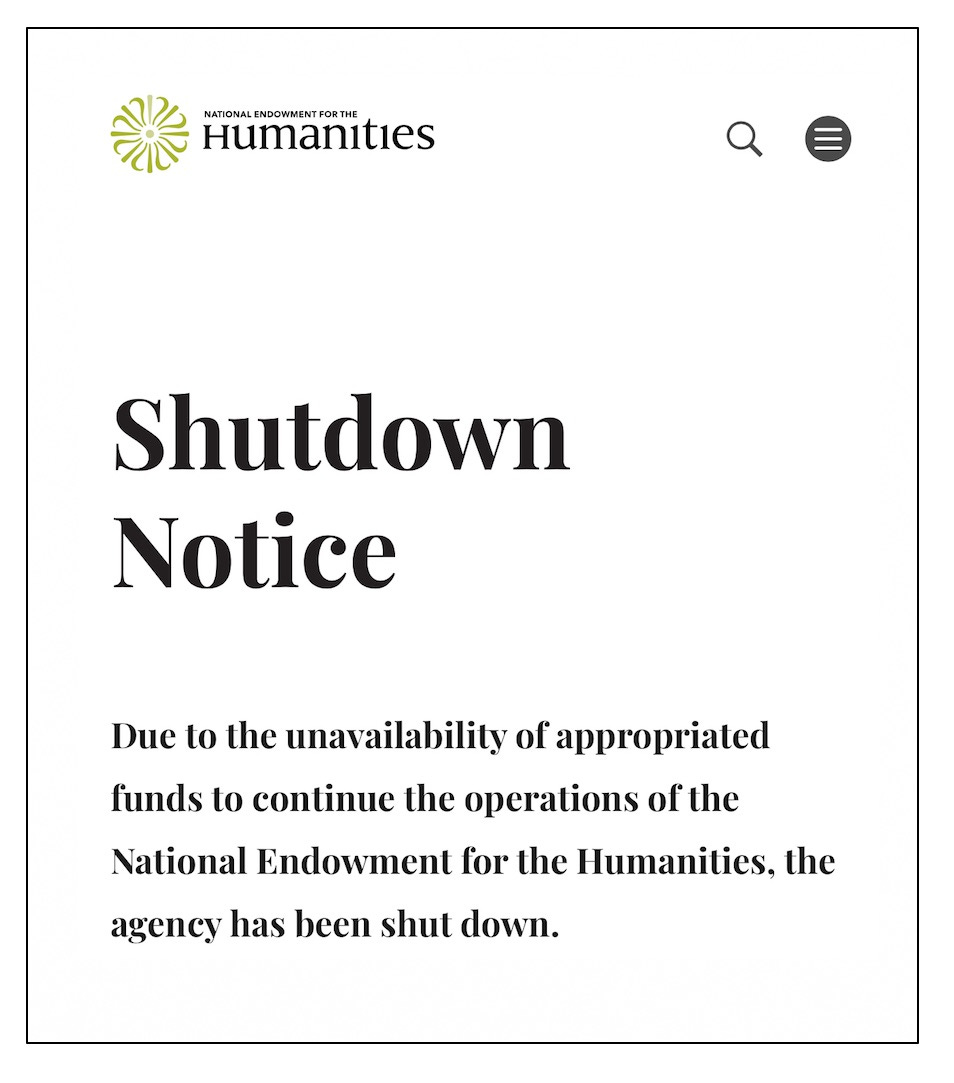

During the period of uncertainty following the President’s first announcement, the endowments continued to accept grant proposals, in the hope that their funding would in the end be approved. Right now, the endowments’ web sites declare them closed for business.

Fortunately for those who write and publish books and run libraries, Congress has not embraced Trump’s position. It approved the 2018 budget last March with a slight increase on 2017 funding levels for the two endowments (supported by Alaska Republican Lisa Murkowski, chairwoman of a crucial Senate appropriations subcommittee). As of early December House leadership was refusing to bring a bill reauthorizing the IMLS through 2025 to the floor, but mobilization by thousands of librarians and library patrons turned its fortunes around and authorization passed both houses in mid-December with bipartisan support, strengthening libraries’ position for the coming budget negotiation for 2019. The 2018 budget not only funded the IMLS but provided significant increases in literacy programs, funding for school libraries, and electronic access to government documents through the Library of Congress.

Public libraries receive the bulk of their funding from state and local governments (making them vulnerable to austerity measures and budget crises at the local level, see below re Kansas), but loss of the IMLS funds would have been a significant blow. More than $150 million of IMLS funds goes directly to the states, which use the funds both to support statewide programs and to give individual grants for services like bookmobiles, summer reading programs, digitization, access to e-books and other technologies, making electronic databases available, and providing computer instruction, homework centers, and outreach programs to underserved readers. The IMLS is obliged by statute to address underserved communities and readers who have difficulty using a library, such as blind and disabled people. According to a letter drafted by the American Library Association, 73 percent of rural libraries report they serve as their community's only free Internet provider.

The struggle to create and preserve arts and humanities funding has some unusual allies. Reagan’s effort to cut arts funding during the “supply-side” austerity measures of the mid eighties were thwarted when a special task force, including his Hollywood colleague Charlton Heston, determined that arts funding performed a valuable service to the nation. Newt Gingrich, who led efforts to eliminate the endowments during the nineties by denouncing works of art by Andres Serrano and Robert Mappelthorpe, recently told The Washington Post that NEH funding enables important historical research and the NEA is valuable for exposing kids to the arts. Municipalities argue that culture drives business and tourism and that federal funding spurs private giving. Kansas provided a laboratory for extreme arts defunding in 2011 when Governor Sam Brownback eliminated the state’s arts funding at a blow with a line-item veto as part of his comprehensive state government scale-down, rendering the state ineligible for federal matching funds. A fraction of the funding was restored the following year, and arts programs hobble on in Kansas with private donations, but the President’s local supporters are divided on his call to eliminate arts funding, and limited-government Republicans lost the Kansas governor’s race in November.

The NEA and the NEH serve book culture mostly at its source, by providing direct grants to writers and scholars for individual projects. But since the culture wars of the nineties the emphasis in the endowments overall has been providing access to the arts and scholarship, particularly to people in underserved communities. Book-related projects funded in 2018 include digitizing archives, supporting library infrastructure, funding exhibitions, editing the papers of Mark Twain, Martin Luther King, and Thomas Jefferson, creating workshops and seminars for teachers, supporting conferences like the Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP) and the American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) gatherings, as well as reading series’ and book festivals. The NEA includes among its goals “ensuring that literary presses and magazines, community-based centers, and national literary organizations complement the trade publishing sector in the shaping of contemporary literature,” but direct grants to publishers are few.

Compared to other countries of course American federal support for the arts is very thin. This approach is usually defended by pointing to the charitable tax deduction (whose effects were minimized in the 2018 tax law); the tax deduction nourishes private support for the arts at levels unseen in other countries. But writing arguably benefits less from arts philanthropy than, say, the visual and performing arts, which are dependent on large institutions. In Europe, by contrast, both at the level of the European Union and in the individual countries, government support for book culture is very robust and widely discussed. As Stephanie Kurschus, in European Book Cultures, observes, European states are committed to maintaining “publishing pluralism” as a bulwark against the threat of cultural conformity due to corporate concentration in the publishing industry. The book industry, they argue, is not simply a business but a guarantor of national and regional cultural identity. She quotes a Finnish report to the effect that maintaining access to ideas is “one of the responsibilities of the democratic state … access to cultural goods such as books is a form of democratic empowerment.” And the Swiss Book Lobby: “Without books, there is no historical memory in modern society, no tradition of cultural values, no systematic reappraisal of the present, no profound understanding of the future—no consciousness of community."

Researchers sited by Kurschus identify a broad range of threats to the book market that will sound familiar. Chains utilize their market power to negotiate favorable discounts, squeezing publishers and authors and undercutting their smaller competition. Concentration by large chains and internet business threatens independent booksellers who tend to be more open to trying out or advocating for new material and to representing a range of tastes. Due to a parallel concentration in journalism, fewer papers review fewer books and tend to focus on bestsellers, like the chains. Libraries, schools, and other institutions suffer from declining book-buying budgets. In consequence, publishers are less likely to take risks or experiment with unpopular or challenging ideas.

In response both to the threats to the market and the perceived importance of books to a healthy society, European governments enact a broad range of supports for the book industry. One of the best known is fixed book pricing (in France, Norway, and Spain, for example, and mentioned by Geoffrey O’Brien in our piece on the vitality of French bookstores). Preventing well-funded competitors from pricing books at a loss protects independent booksellers from price-gouging and also retains for publishers the proceeds from bestsellers to reinvest in a broader diversity of acquisitions. Fixed pricing is popular with independent booksellers and publishers but not always with consumers: Switzerland withdrew a fixed-pricing system by referendum in 2012.

Some countries have also offered books tax protection. Although the European sales tax, the Value Added Tax, or VAT, is supposed to apply uniformly across EU countries, the EU tolerates exemption or discounting for books country by country, arguing that, because of language differences, books are bound to their local markets and variable pricing would not undercut trade. Book sales soared in Sweden when they reduced the VAT on books from 25 percent to 6 percent in 2002. England, for example, does not intervene in the book industry but it does give a discount on the VAT and supports private funding for the arts with matching grants.

Norway, Greece, Sweden, and Slovenia purchase books at scale for libraries, in some cases buying out the runs for small, niche books and offering a significant cushion of support for small publishers. Finland gives grants to small municipalities to support library purchasing. Spain gives away free textbooks; Slovenia gives a free picture book to every newborn; in the Netherlands books in Braille are shipped for free.

Switzerland and Austria have programs supporting development of book marketing and distribution at home and abroad, and between languages, aimed at small and independent publishers. Switzerland also has a fund allowing small publishers to obtain loans at a favorable rate. The French National Book Center provides no-interest loans to open bookstores, and French municipalities provide free space and tax benefits to booksellers. French booksellers that meet certain standards in the breadth or quality of their offerings, or develop innovative distribution methods, are eligible for grants.

Europe has a particular interest in supporting its various language cultures, and mutual understanding among them, and most European countries have strong public support for translation into and out of their languages. These grants incidentally give a significant boost to American publishers of literature in translation. Part of the effort here is to maintain “bibliodiversity” against the overwhelming commercial influence of English. Small countries give grants to publishers for maintaining access to their local literatures: Estonia, Bulgaria, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Switzerland, Finland, Luxembourg. Some governments, such as Bulgaria’s, give grants aimed at filling in the gaps in their national literatures. The French National Book Center offers one of the most comprehensive programs of translation support. It covers transportation costs, assistance to booksellers abroad, and professional development for translators, in addition to assistance for translation into and out of French. French publishers are among the broadest in their offerings, geographically, as a result (also noted by Geoffrey O’Brien). Switzerland, home to several languages, even includes a commitment to cultural diversity in its constitution.

UNESCO calls for all countries to develop a book policy that envisions a global conception of the book industry, recommending “preferential postal rates and elimination of customs taxes or other import taxes; strengthen[ed] distribution mechanism[s], modernization of bookshops and support to nearby bookstores; adoption of the sector of code of conduct in the field of commercial practices [and] measures to encourage export.” (The US, incidentally, does have a preferential postal rate for books, after which we are named! It’s now called “Media Mail.”)

Fortunately the threat to our existing system of supports for books and the life of ideas does not at the moment seem grave, in light of congressional fidelity to the endowments and the library institute, but as we head into another political season, and one in which models for the role of federal government might seem to be getting fresh consideration, those of us who are committed to book life might consider whether we should advocate for a palette of programs dedicated to its health and the sustenance it provides for a well nourished and multidimensional culture. Such a palette might include policies that challenge concentration and monopoly in book publishing and selling and media platforms, constrain predatory pricing, and support small business. Bookseller Lexi Beach, the co-owner of Astoria Bookshop in Queens, made the case recently that readers should lobby legislators for policies that buffer bookstores and other small retail business from an inflated real-estate market. Americans are perhaps less comfortable than those from other nations with the idea of promoting a “national culture,” and the dangers of official intervention in the thinking life are visible to us, but also visible these days are the dangers of unbridled commercial forces that harness our worst instincts and obliterate the delicate growth of the ideas and debates that may renovate us.

Most of the information here about European book policies is drawn from Stephanie Kurschus, European Book Cultures.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing to your in-box book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers, plus a few other treats, such as this one, for followers of our free updates and visitors to our site. Please consider a subscription! Or give a gift subscription to a friend!

Recent reviews include Joy Williams on Richard Powers and Adam Kirsch on rabbinic law. Coming up we have Edward Mendelson on the history of typography and Judith Newman on the foibles of the royals.

Book Post is a medium for ideas designed to spread the pleasures and benefits of the reading life across a fractured media landscape. Our paid subscription model allows us to pay the writers who write for you. Our goal is to help grow a healthy, sustainable, common environment for writers and readers and to support independent bookselling by linking directly to bookshops across the land and sharing in the reading life of their communities. Book Post’s winter partner bookstore is Greenlight. Spend a hundred dollars there in person or virtually, send us the evidence, and we’ll give you a free one-month subscription to Book Post. And/or

follow us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram.

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like”