Diary: Michael Robbins, World in Flames

I grew up in Colorado in the late seventies and eighties, and there was forest everywhere. There was not fire everywhere. Each day the school bus passed one of the common wooden signs depicting Smokey Bear indicating the day’s “fire danger.” Smokey, holding a shovel for some reason, informed me that only I could prevent forest fires, which seemed unlikely.

I liked those signs. They appeared to be made of real wood, and the differently colored danger-level boards—low, moderate, high, very high, extreme—had to be slotted in by hand. I would imagine the scene at the ranger station: a thin guy with a green hat (Ranger Smith from the Yogi Bear cartoons) surveys the forest through binoculars, turns to a subordinate, and says, “Go change the level on Highway 67 to ‘moderate.’” (I know this is not how it worked.)

Anyway I never saw a single wildfire (as the signs began to call forest fires in 2001). You heard about the occasional fire, or saw smoke from a great distance, but this was infrequent and carried no sense of menace. Unbroken pine forest rose fifty feet from our back door, and though I wandered those woods often I never thought twice about how easily they would burn. And, in fact, they would have burned much less easily than they would today (though Google Maps informs me they are gone, replaced by houses).

The world, of course, was cooler then. Global temperature has increased at an average rate of 0.32 °F (0.18 °C) per decade since 1981. You know this. Exxon knew it, too, in 1981. And here we are, a dog sitting in a burning house, saying, “This is fine.”

•

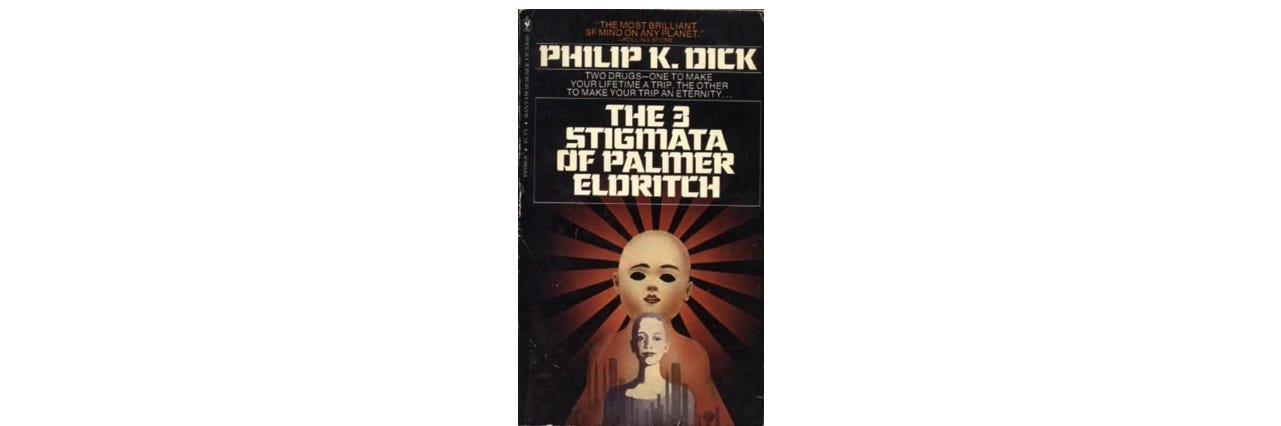

Though the terms “acid rain” and “greenhouse effect” were in the air during my childhood, the first inkling I had of what all this might mean came not from the news but from science fiction, back before the two became indistinguishable. I read just about anything when I was a kid, but sci-fi and fantasy made up the greater part of my non-comics curriculum. I didn’t know anything about the authors I read. Philip K. Dick—just another name. But at ten or eleven I was powerless to resist a cool cover and eerie title:

The plot of The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch is too insane to summarize. Like most of Dick’s novels, it’s about the nature of reality, which might be an illusion. There’s a drug that turns you into a Barbie-like doll in a toy “layout” world, for starters—it’s unclear whether this “translation” is real or hallucinated. What does seem to be real is the heat.

The novel is set, rather presciently, in 2016. Outside it is “too hot for human endurance” except where “antithermal protective shields” shelter those who must scrabble from door to “autonomic cab” (a driverless floating taxi), from cab to office or “conapt” (condominium apartment). “Things were hotter and wetter,” Dick writes. Glaciers have retreated, record temperatures are regularly broken, the oceans are evaporating, and mailmen swiftly complete their appointed rounds before the sun rises.

•

Well, yesteryear’s science fiction is today’s nonfiction—specifically, I have just read Jeff Goodell’s The Heat Will Kill You First and John Vaillant’s Fire Weather. Along with Stephen J. Pyne’s The Pyrocene from 2021, these books constitute a horrifying and extremely depressing primer on our age of heat and fire. Pyne goes deep, telling the story of fire from the beginning, 450 million years ago, to the wildfires that ravaged California and Australia in 2020. After a much hastier review of this story, Vaillant goes granular (a little too granular) on the 2016 Fort McMurray fire in Alberta, Canada. Goodell ranges all over the place, from air conditioning to polar bears to heat waves, melting ice to city planning to mosquitoes to wildfire, thus providing an excellent overview of the many different ways in which a heating world messes with life.

Both Goodell and Vaillant write the usual journalistic prose (Vaillant: “The shock was palpable and traumatizing”; Goodell: “Writing this book has been an adventure to unexpected places”), and the art of copy editing appears to be dead (Goodell prints Yeats’s lines—from one guess which poem—as if the poet had abhorred punctuation; he writes “whom” when “who” is called for. Vaillant writes “who” when “whom” is called for, misuses the phrase “beg the question,” and twice misspells the title of Lucretius’s De rerum natura).

But you don’t read this stuff for style. You’ll learn plenty of uncomfortable truths from these books, many of them straight out of disaster movies. In 2021, the temperature in Jacobabad, Pakistan—a country of 220 million people and fewer than a million air conditioners—reached 126 degrees every day for more than a week. Alberta’s Chisholm fire of 2001 released so much energy that some experts in Washington thought Canada had detonated a nuclear bomb. “Parisians have a long history of being ignorant about climate.”

•

“The Earth is getting hotter,” Goodell writes, “due to the burning of fossil fuels.” Pyne says that “fossil fuel combustion” has rendered the planet “increasingly uninhabitable.” Hominids have been burning fuels for hundreds of thousands of years. It wasn’t until James Watt invented his steam engine in 1769 that we became capable of burning fuels at a rate sufficient to bring about global ecological catastrophe. As Andreas Malm relates in his indispensable Fossil Capital, industry turned from hydraulic to coal power in order to lower wages and tighten control of labor, rather than to improve productivity.

Our authors know these things, though only Vaillant ventures into the economic weeds, as he must, since Fort McMurray was built around the largest reservoir of bitumen on earth. Industrial profiteering, not individual consumption, has driven catastrophic warming, and the modern state is designed to manage, not impede, capital flows. Each of these books, though, ends on an ironically depressing note of optimism, perhaps because books that conclude “we’re fucked” tend not to sell. Goodell writes, “I met people while researching this book who believe that the political and economic systems” of modern society “are unsalvageable.” I mean, yeah. It’s alarming that more people don’t arrive at this conclusion, including Goodell himself, who offsets his litany of the insane consequences of extreme heat with palliative fantasies of “decarbonization,” ignoring the fundamental law of capital, which is expansion in search of further accumulation. As long as oil produces larger returns than “clean” energy, Exxon will keep drilling, perhaps behind a green facade. The current UN climate conference is being hosted by the head of a gulf state oil company, which is like putting the lions in charge of the zoo. This will end in collapse, not peaceful transition.

Vaillant likes to quote poetry, from a narrow, entirely male syllabus—besides Lucretius, he cites Homer, Ovid, Shakespeare, Milton, Borges, Frost, William Carlos Williams, and Seamus Heaney. (The results can be ludicrous: the evacuation of Fort McMurray with a great boreal fire bearing down at incredible speed on all sides gave “a whole new meaning to the poet Andrew Marvell’s line, ‘Had we but world enough and time.’”) I’ll stick with science fiction. “It’s going to be hotter,” one of Dick’s characters says in Palmer Eldritch. “Every day. Isn’t it? Until finally it’s unbearable.”

Read Stephen Pyne in Book Post on fire and John Terborgh on insect collapse.

Michael Robbins is the author of three books of poems, most recently Walkman, and a book of essays, Equipment for Living: On Poetry and Pop Music. He last wrote for Book Post on the fate of nonhuman life.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world. Become a paying subscriber to support our work and receive our straight-to-you book posts. Coming soon: John Banville on Labatut’s von Neuman, Christian Caryl on Werner Herzog.

Square Books in Oxford, Mississippi, is Book Post’s Winter 2023 partner bookstore! We partner with independent bookstores to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. We’ll send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 with our partner bookstore during our partnership. Send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com. Read more about Square here in Book Post. And buy a Book Post Holiday Book Bag for a friend and send a $25 gift e-card at Square with a one-year Book Post subscription!

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Notes, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa

If you liked this piece, please share and tell the author with a “like.”

I believe The Three Stigmata was the first PKD novel I ever read. Someone else might reference it in a post on post-humanism and post-humanist billionaires like Peter Thiel and Elon Musk. It's Musk who's got a hard-on for the colonization of Mars, which is where PKD's characters spend their days transubstantiating with Perky Pat and her boyfriend. In the novel, it's posited that Palmer Eldritch is a surrogate for beings from, I think, Proxima Centauri, and it seems fairly plausible that Musk is a surrogate for a being from the Russian Federation.