Review: Michael Robbins on translations of Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Having just finished rereading Metamorphoses in different translations, the author arrives at various grouchy conclusions about the art of translation

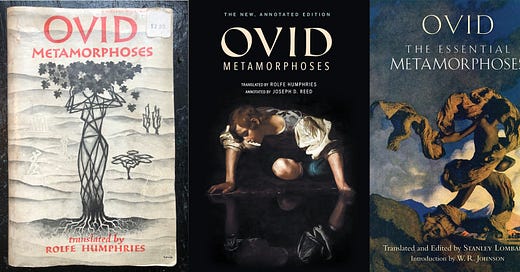

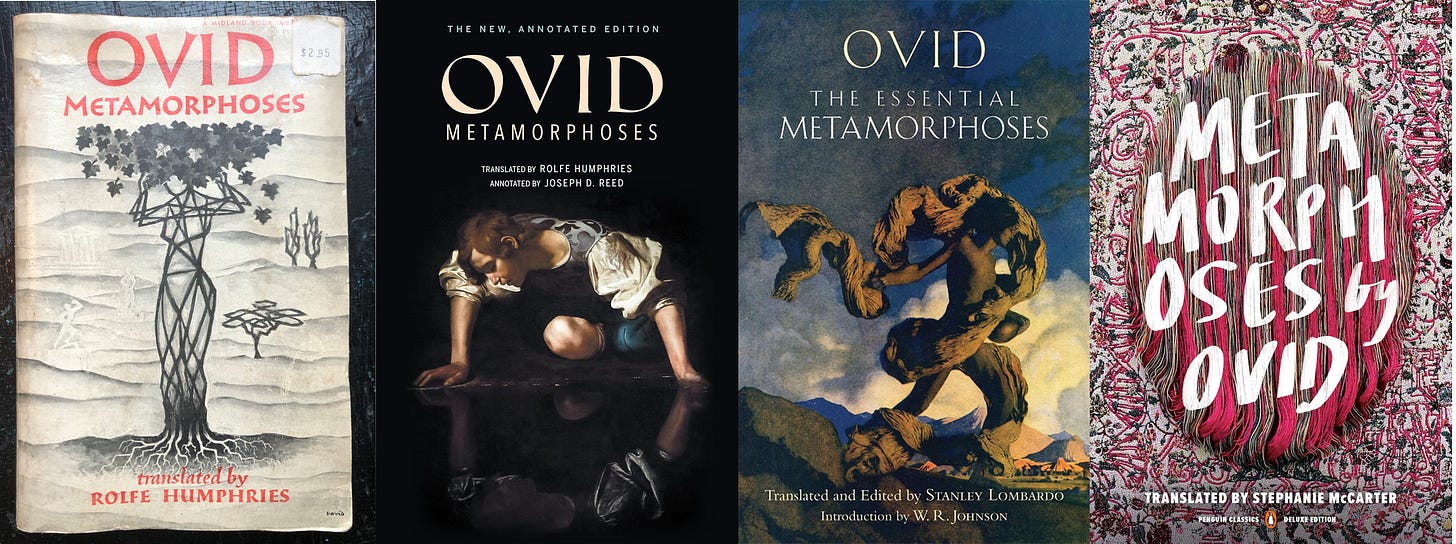

Ann’s copy of Rolfe Humphries, which seems to have gotten a bit wet during some transformation or other, and other editions of Metamorphoses considered in this post

It would suck to get turned into a tree. Such was my main takeaway from Ovid’s Metamorphoses in college. Now, in my early fifties, I’m like, “Ah, to be a tree, how peaceful.” (The poem is a series of tales of transformations—nymph into reed, girl into tree, man into flower, man into stag, etc.—usually effected by the gods, often involving sexual violence.) Having just finished rereading Metamorphoses in different translations, I have arrived at various grouchy conclusions about the art of translation.

Anthony Madrid, il miglior fabbro, has preceded me here, so I shan’t attempt to replicate his thoughts. Nor do I expect to be saying anything especially novel. Just offering some musings—a word with no etymological link to the Muses, whom Ovid invokes at the very end of his long, unclassifiable poem: “Reveal to me now, Muses, divine ones / Present to poets (for you know, and time / Does not cheat you) …”

That’s how Stanley Lombardo renders it, anyway, in his 2010 edition. Lombardo’s virtue is plainness. Zero poetry; elegant, accurate phrasing. The above is pretty close to the Latin, as far as I can tell (I can’t read Latin but I can suss it out with the help of commentary). I came to rely on Lombardo most, drifting further and further from Rolfe Humphries, whose classic translation (1955) I started out with. Here’s what Humphries does with the invocation: “And now, O Muses, helpers of the poets / You knowers and rememberers, aid the telling …”

“Aid the telling” is more beguiling than “reveal to me.” Humphries’s version is by far the most poetic I consulted—which is to say, it reads most like a poem written in English. Consider the lovely concluding lines of Book Two (Jupiter in the form of a bull kidnaps Europa):

And he rises, ever so gently, and slowly edges

From the dry sand toward the water, further and further,

And swimming now, with the girl, trembling a little

And looking back to the land, her right hand clinging

Tight to one horn, and the other resting easy

Along the shoulder, and her flowing garments

Filling and fluttering in the breath of the sea-wind.

This is fine writing. Lombardo, who has Europa’s “clothes fluttering in a stiffening breeze,” is flat and ungainly.

The problem with Humphries is you just can’t trust him, as Joseph Reed’s notes in Indiana University Press’s annotated edition (2018) make clear. Notice that he elides what Ovid says in his invocation about how the Muses aren’t deceived by the passage of time (vetustas, ancient times, antiquity). In Book 8, after Althea has caused the death of her son Meleager, Ovid’s speaker intervenes in the first person. Humphries describes Meleager’s sisters’ lamentations thus: “No poet has the power / To tell the story truly, those poor sisters / Praying, for what? beating and bruising their breasts.” Reed:

Humphries has compressed and obscured Ovid’s version of an old, grandiose epic motif, more literally rendered “Not if a god had granted me one hundred mouths resounding with one hundred tongues and a talent equal to the task and all of Helicon [the Muses’ mountain] might I follow the sorrowful prayers of his wretched sisters to the end.” It is first found in Iliad 2.488-90, introducing the long Catalogue of Greek Ships.

That’s exactly the kind of shit I want to know! And Humphries just sails on by. Lombardo, on the other hand, gives:

Not if some god

Gave me a hundred speaking mouths, sheer genius,

And all Helicon has, could I ever capture

The lamentation of his wretched sisters.

OK, not as powerful as Reed’s crib; Lombardo loses the emphasis of the repetition in “one hundred mouths with one hundred tongues,” and “speaking mouths” is just awkward. But at least we have a sense of the figure Ovid uses—at least we know he uses one.

There are a hundred such omissions or changes in Humphries’s translation. Sometimes he flat-out gets the Latin wrong. So why read him at all? Well, because Lombardo has a vice, too, a dreadful one: cutesiness. He has Medea develop a “heavy crush” on Jason. Are we in ancient Greece or Riverdale? Myrrha tricks her father into having sex with her and leaves the chamber “carrying in her womb … a maculate conception.”

Sometimes one can play their vices off against each other—Lombardo might catch some nuance Humphries neglects; when Lombardo gets too cute, Humphries might give you a less annoying expression—but sometimes they clash, neither completely satisfactory, as when Humphries totally neglects Ovid’s wordplay about Sleep in Book 11. Sleep is said to have “shook himself off himself” in the Latin—Sleep personified as a god, both the cause and the effect. Humphries just says he “roused himself.” Lombardo is much better, but he just can’t resist introducing a discordant cutesy note: Sleep “shook himself free of, well, himself.” That “well” is un-Ovidian. Ol’ Naso rarely overplays his hand; he trusted the reader to notice his effects.

This is how I respond to translations: “it’s fine except for this” is my highest recommendation. (I’m currently reading Richard Howard’s translation of The Charterhouse of Parma, marveling at Howard’s felicity—but why render the characters’ names, which Stendhal deliberately Gallicized, in their “correct” Italian forms? just because Scott Moncrieff did in 1925?)

There is no such thing as a faultless translation. I just prefer Lombardo’s and Humphries’s faults to those of the other renditions I consulted. Charles Martin’s 2010 version, for instance, is readable and often eloquent (“O Muses, who attend upon the bards, / reveal (for you have knowledge of these things, / nor do the ages, stretching out forever, / betray your memories)”). But Martin is also given to cutesiness—indeed, he goes full cringe, as my students have it. In Book 5, the singing contest between the Muses and the Pierides is rendered—atrociously—as a rap battle between the Muses and “the P-Airides.” And Martin is no Rakim—he’s not even a Macklemore: “So take the wings off, sisters, get down and jam / And let the nymphs be the judges of our poetry slam!” Dad, stop, you’re embarrassing me.

Stephanie McCarter’s 2022 edition is a tragedy, because the translation is very good (“Now, Muses, powers well-disposed to bards, / (for you know—ancient times do not escape you)”). What kills it is the layout. Unaccountably, someone has made the indefensible decision to print each episode of metamorphosis as a separate chapter, with its own heading. So instead of the usual fifteen books (with perhaps a list of the episodes in a headnote, as in Lombardo), McCarter’s Metamorphoses contains dozens of subdivisions. Book One alone is divided into sixteen sections. This makes the book almost unreadable for me and unusable in class, for it gives the erroneous impression that these narratives are self-contained, perhaps interchangeable. In fact one of the delights of Ovid is his ingenuity of connection—his subtle transitions from one crazy transformation to the next, the linkages and echoes between episodes. Isolating each episode is especially harmful to the many “nested” stories, in which a narrator recounts a story she got from another narrator, who was recounting something someone once told her, who heard it from someone else, and so on, as in the tale of Orpheus’s tale of Venus’s tale of Atalanta. This isn’t incidental—as Reed says, the Metamorphoses “takes storytelling itself as one of its topics.” Ovid (Lombardo): “And, as usually happens, / The latest story brings up earlier ones / That people retell.”

I looked at a few more translations that failed to make enough of an impression to merit comment. But I reserve a special raspberry for David R. Slavitt’s version. It’s bad enough that he makes Ovid allude to English poets (like Shakespeare: “Now that you’ve seen a naked goddess, go / and tell whomever you will …”); Humphries, Lombardo, and Martin do this too, though less ostentatiously. What’s unforgivable is that he occasionally intrudes upon Ovid’s text in his own voice to offer editorial comment (Martin does this too, though less ostentatiously): “This story, a somewhat mannered performance, / is one of those nice rhetorical set pieces Ovid loved”; “But it’s risky, even for Ovid, to try to do Orpheus’s voice.” This is cutesiness raised to the highest power. This is the apotheosis of cutesiness, a veritable shrine to cutesiness. You see, Slavitt explains, reading is a matter of “collaboration” between reader and author. Sure. But collaborate on your own dime.

I sound like a fuddy-duddy holed up with the Loeb Classical Library. But I admire Ted Hughes’s Tales from Ovid, Robert Lowell’s Imitations, Jack Spicer’s After Lorca, and War Music, Christopher Logue’s magnificent “account” of The Iliad. All of these commit madcap liberties with the source text. But none of them is billed as a straight “translation”—they’re published under the translators’ names.

I’m not even opposed on principle to a translator’s running wild in a poet’s fields, as long as it’s done well. Paul Schmidt’s Complete Works of Rimbaud has many charms. And according to the internet, Aristophanes, in The Clouds, wrote, “The vices of your age are stylish today.” Except he didn’t. Translator William Arrowsmith invented the line out of whole cloth. But it sounds like Aristophanes. And good, as Madrid concludes, is good.

Michael Robbins is the author of three books of poems, most recently Walkman, and a book of essays, Equipment for Living: On Poetry and Pop Music. He has written for Book Post on Rilke, Marcel Proust, Paul Muldoon, Allen Ginsberg, apocaplypse by fire, “Nancy,” the destruction of animals, and cheesy reading.

Book Post is a by-subscription book review delivery service, bringing snack-sized book reviews by distinguished and engaging writers direct to our paying subscribers’ in-boxes, as well as free posts like this one from time to time to those who follow us. We aspire to grow a shared reading life in a divided world. Become a paying subscriber to support our work and receive our straight-to-you book posts. Recent reviews: Yasmine El Rashidi on the evolving contemporaneity of the Egyptian literary diary; Geoffrey O’Brien on life merging into work in the films of Agnès Varda; and Christopher Benfey on a convention-defying nineteenth-century literary couple.

Dragonfly and The Silver Birch, sister bookstores in Decorah, Iowa, are Book Post’s Fall 2024 partner bookstores! We partner with independent booksellers to link to their books, support their work, and bring you news of local book life across the land. Read more about Dragonfly and Silver Birch in our announcement! We send a free three-month subscription to any reader who spends more than $100 at our partner bookstore during our partnership. To claim your subscription send your receipt to info@bookpostusa.com.

Follow us: Instagram, Facebook, TikTok, Notes, Bluesky, Threads @bookpostusa

well i guess your making me learn latin then professor